The frontier settlement of New Madrid in the Missouri territory, was founded at the end of the 18th century, in 1789. At the time of the New Madrid Earthquake the settlement had several thousand inhabitants of settlers and Native-Americans. New Madrid sat on the fringes of the western settlement of the United States. [1]

The typical settler lived in a log cabin type structure without any improvements. Travel was accomplished by horse and or horse drawn wagon on crude wagon trails. Where swaps existed on the banks of the Mississippi river, wood planks were occasionally lain down on top of the mud to accommodate travel. The Mississippi river, its tributaries and associated lakes allowed for river travel and commerce to take place. [1]

The four main shocks that shook the New Madrid area occurred over a three and a half month period, beginning in December, 1811. Current day estimates place the magnitude of the four main shocks at possibly 8.4 on the Richter Scale, or greater. [1]

At the time, the sparseness of the population probably accounts for the low loss of life. The aftereffects of the series of earthquakes are described by Eliza Bryan in a letter she penned as an eyewitness to the events of the day. Bryan wrote; “We were constrained by the fear of our houses falling to live twelve or eighteen months, after the first shocks, in little light camps made of boards; but we gradually became callous, and returned to our houses again. Most of those who fled from the country in the time of the hard shocks have since returned home.” [2]

Bryan’s description tells us that many residents of the area abandoned their homes to live in makeshift shacks, out of fear that their log homes would collapse during subsequent aftershocks. Others actually migrated out of the area, only to return months later. The fear of falling homes must have been justified, as most homes of the time were not of a rigid type of construction, but rather of heavy logs that were notched at both ends, and then placed atop one another. The logs were held in place by weight and friction. [3]

The roofs of many cabins were constructed of sod and earth. The jarring and shaking of an earthquake could easily cause the heavy logs to bounce apart and a stout roof to cave in. [1]

Other accounts tell us that trees toppled over, and that the direction of the Mississippi river change course for at least twenty-four hours on one occasion, to fill in an earthquake caused sinkhole that would later become Reelfoot Lake. As the Mississippi River ran upstream, boats used to bring supplies in and take goods out, broke from there moorings and drifted into one another to stack up like cordwood. Other boats were washed up onto the riverbanks.

The damage to settler’s homes and to property was significant enough to prompt Congress to pass the Disaster Relief Act of 1815. [1]

The economic hardship and fallout from the New Madrid Earthquake lasted another fifty years. Author and Historian, Jay Feldman wrote of the effects of the New Madrid Relief Act of 1815, which follows:

“On February 17, 1815 [three years after the strongest earthquakes in U.S. history], Congress passed the New Madrid Relief Act, the first federal disaster relief act in U.S. history. Unfortunately, the act itself turned out to be a disaster.

The legislation provided for residents whose land had been damaged in the earthquakes to trade their land titles for a certificate that would be good for any unclaimed government land for sale elsewhere in the Missouri Territory. The only restriction was that the new grants had to be between 160 and 640 acres, regardless of how much or little land a person had previously owned. Well-intentioned though the legislation was, it did little to help the residents of the New Madrid area.

Communications being what they were, word of the New Madrid Relief Act did not reach the New Madrid area for months. News did reach St. Louis and other places, however, and speculators were soon beating a hasty path to New Madrid and buying up land for a pittance from unsuspecting locals. Of the 516 certificates issued for redemption, only twenty were held by the original landowners. Three hundred and eighty-four certificates were held by residents of St. Louis, some of whom had as many as forty claims. Adding insult to injury, many banks in Missouri failed, making the Missouri banknotes used to pay for these claims worthless. Governor Clark himself was not above profiting from the situation, as he authorized two of his agents, Theodore Hunt and Charles Lucas, to purchase land in the New Madrid area. Meanwhile, opportunists in New Madrid caught on to what was happening and began selling their land titles many times over. Before too long, the term "New Madrid claim" came to be synonymous with fraud.

Litigation over the resulting land claims tied up the courts for over twenty years, with hundreds of fraudulent claims being pressed. Over the next three decades, Congress passed three more pieces of legislation to try and straighten out the mess. The last case stemming from the New Madrid Relief Act was finally settled in 1862, fifty years after the earthquakes of 1811–12—by which time the frontier had moved a thousand miles west.” [6]

The typical settler lived in a log cabin type structure without any improvements. Travel was accomplished by horse and or horse drawn wagon on crude wagon trails. Where swaps existed on the banks of the Mississippi river, wood planks were occasionally lain down on top of the mud to accommodate travel. The Mississippi river, its tributaries and associated lakes allowed for river travel and commerce to take place. [1]

The four main shocks that shook the New Madrid area occurred over a three and a half month period, beginning in December, 1811. Current day estimates place the magnitude of the four main shocks at possibly 8.4 on the Richter Scale, or greater. [1]

At the time, the sparseness of the population probably accounts for the low loss of life. The aftereffects of the series of earthquakes are described by Eliza Bryan in a letter she penned as an eyewitness to the events of the day. Bryan wrote; “We were constrained by the fear of our houses falling to live twelve or eighteen months, after the first shocks, in little light camps made of boards; but we gradually became callous, and returned to our houses again. Most of those who fled from the country in the time of the hard shocks have since returned home.” [2]

Bryan’s description tells us that many residents of the area abandoned their homes to live in makeshift shacks, out of fear that their log homes would collapse during subsequent aftershocks. Others actually migrated out of the area, only to return months later. The fear of falling homes must have been justified, as most homes of the time were not of a rigid type of construction, but rather of heavy logs that were notched at both ends, and then placed atop one another. The logs were held in place by weight and friction. [3]

Typical Log Cabin Construction Technique [4]

The roofs of many cabins were constructed of sod and earth. The jarring and shaking of an earthquake could easily cause the heavy logs to bounce apart and a stout roof to cave in. [1]

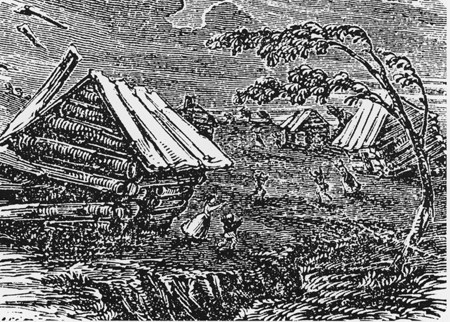

The Great Earthquake at New Madrid. A nineteenth-century woodcut from Devens' Our First Century (1877)

Other accounts tell us that trees toppled over, and that the direction of the Mississippi river change course for at least twenty-four hours on one occasion, to fill in an earthquake caused sinkhole that would later become Reelfoot Lake. As the Mississippi River ran upstream, boats used to bring supplies in and take goods out, broke from there moorings and drifted into one another to stack up like cordwood. Other boats were washed up onto the riverbanks.

The damage to settler’s homes and to property was significant enough to prompt Congress to pass the Disaster Relief Act of 1815. [1]

The economic hardship and fallout from the New Madrid Earthquake lasted another fifty years. Author and Historian, Jay Feldman wrote of the effects of the New Madrid Relief Act of 1815, which follows:

“On February 17, 1815 [three years after the strongest earthquakes in U.S. history], Congress passed the New Madrid Relief Act, the first federal disaster relief act in U.S. history. Unfortunately, the act itself turned out to be a disaster.

The legislation provided for residents whose land had been damaged in the earthquakes to trade their land titles for a certificate that would be good for any unclaimed government land for sale elsewhere in the Missouri Territory. The only restriction was that the new grants had to be between 160 and 640 acres, regardless of how much or little land a person had previously owned. Well-intentioned though the legislation was, it did little to help the residents of the New Madrid area.

Communications being what they were, word of the New Madrid Relief Act did not reach the New Madrid area for months. News did reach St. Louis and other places, however, and speculators were soon beating a hasty path to New Madrid and buying up land for a pittance from unsuspecting locals. Of the 516 certificates issued for redemption, only twenty were held by the original landowners. Three hundred and eighty-four certificates were held by residents of St. Louis, some of whom had as many as forty claims. Adding insult to injury, many banks in Missouri failed, making the Missouri banknotes used to pay for these claims worthless. Governor Clark himself was not above profiting from the situation, as he authorized two of his agents, Theodore Hunt and Charles Lucas, to purchase land in the New Madrid area. Meanwhile, opportunists in New Madrid caught on to what was happening and began selling their land titles many times over. Before too long, the term "New Madrid claim" came to be synonymous with fraud.

Litigation over the resulting land claims tied up the courts for over twenty years, with hundreds of fraudulent claims being pressed. Over the next three decades, Congress passed three more pieces of legislation to try and straighten out the mess. The last case stemming from the New Madrid Relief Act was finally settled in 1862, fifty years after the earthquakes of 1811–12—by which time the frontier had moved a thousand miles west.” [6]

[1]Environmental Geology Volume 16, Number 1 / July, 1990

J.D. Rockaway - The great New Madrid, Missouri (U.S.A.) Earthquake of 1811–1812 pp 29-34

[2]The Virtual Times - The New Madrid Earthquake http://www.hsv.com/genlintr/newmadrd/accnt1.htm

[3] Log Cabin Construction http://architecture.about.com/od/periodsstyles/a/logcabins_2.htm

[4] Image: http://z.about.com/d/architecture/1/G/Z/H/logcabin-construction.jpg

[5] Image: http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/1/11/New_Madrid_Erdbeben.jpg

[6] When the Mississippi Ran Backwards: Empire, Intrigue, Murder, and the New Madrid Earthquake, by Jay Feldman (Free Press, 2005), p. 236

No comments:

Post a Comment